Architecture Against the Apocalypse: Designing the Climate-Resilient City

For centuries, the primary struggle of architecture was against gravity. Today, it is against the climate. The abstract threat of rising global temperatures has materialized into a series of visceral, recurring disasters: record-breaking heatwaves that turn cities into ovens, atmospheric rivers that unleash catastrophic floods, and wildfires that consume entire communities. In the face of this new reality, the design of our cities and buildings is no longer just a matter of aesthetics or efficiency; it is a matter of survival. A new discipline is emerging at the intersection of architecture, engineering, and ecology: climate-resilient design. It is the urgent work of retrofitting our present and reimagining our future for a world that is hotter, wetter, and more extreme.

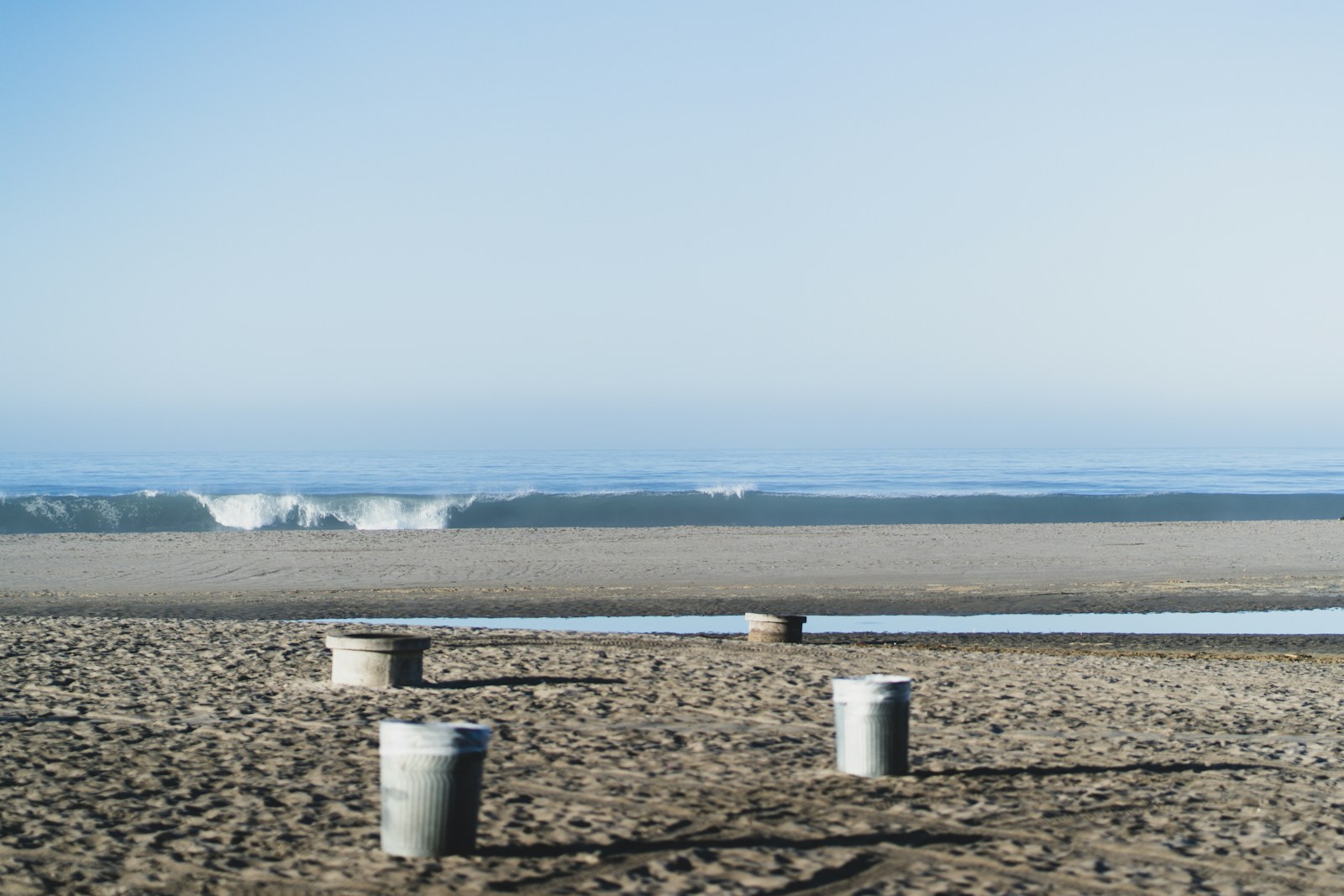

The first front in this battle is against water. As sea levels rise and rainfall becomes more intense, coastal and riverside cities face an existential threat. The old paradigm of "grey infrastructure"—concrete seawalls and channels designed to fight water and divert it away as quickly as possible—is proving to be brittle and inadequate. The new approach is "green infrastructure," which seeks to work with water, not against it. This means designing "sponge cities" with permeable pavements, green roofs, and bioswales that can absorb, filter, and store stormwater instead of being overwhelmed by it. In flood-prone areas, it means a shift towards amphibious architecture—buildings that are designed to float on rising floodwaters—and elevating critical infrastructure like power stations and hospitals above projected flood levels.

The second front is against heat. The "urban heat island" effect, where concrete and asphalt absorb and radiate solar energy, makes cities significantly hotter than surrounding rural areas. This is a deadly threat during heatwaves, particularly for vulnerable populations. Climate-resilient architecture combats this with a focus on passive cooling strategies. This includes using light-colored, reflective materials for roofs and pavements to reduce heat absorption, a modern application of the whitewashed buildings of the Mediterranean. It means incorporating extensive tree canopies and green spaces into the urban fabric to provide shade and evaporative cooling. And it means designing buildings with better natural ventilation, brise-soleils (permanent sunshades), and green facades that can significantly reduce the need for energy-intensive air conditioning.

Beyond individual buildings, resilience requires a systems-level approach to urban infrastructure. A city is only as resilient as its power grid and water supply. The increasing frequency of extreme weather events has exposed the vulnerability of our centralized energy systems. A single downed transmission line can black out millions of homes. The solution lies in decentralization: creating neighborhood-level "microgrids" that can disconnect from the main grid and operate independently during an emergency, powered by local sources like solar panels and battery storage. This ensures that critical facilities like hospitals, cooling centers, and communication networks can remain operational even when the wider grid fails.

This transition is not just a technical challenge; it is a social and economic one. Retrofitting an entire city is a monumental task that requires massive investment and political will. There are also critical questions of equity. Climate impacts disproportionately affect low-income communities, which are often located in the most vulnerable areas and have the fewest resources to adapt. A truly resilient city must ensure that these communities are not left behind, prioritizing investment in green infrastructure and resilient buildings in the neighborhoods that need them most.

The work of climate-resilient design is a race against time. We are no longer designing for a stable, predictable climate, but for a future of escalating shocks. It forces us to be more innovative, more integrated, and more humble in our relationship with the natural world. The architects and engineers on the front lines of this discipline are not just designing buildings; they are building arks, crafting the physical and social structures that will allow our communities to weather the coming storm.