The Argosy Debates: Is Deep-Sea Mining a Necessary Evil for the Green Transition?

Editor's Note: The global transition to electric vehicles and renewable energy requires a staggering quantity of critical minerals. As land-based mines struggle to keep up, a new and controversial frontier has emerged: the deep ocean floor. Is harvesting these resources an unavoidable step in saving the climate, or an environmental catastrophe in the making?

The Pragmatic Case for the Abyss

By Anthony Min

The climate crisis requires us to make difficult choices, not emotionally satisfying ones. The green transition is not powered by good intentions; it is powered by lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese. The demand for these metals is non-negotiable if we are serious about electrifying our global vehicle fleet. The only real question is: where do we get them?

Currently, a significant portion of the world's cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where mining is plagued by child labor and horrific working conditions. Nickel mining in places like Indonesia contributes to massive deforestation. These are not abstract problems; this is the real-world cost of our current supply chain.

Deep-sea mining offers a rational, albeit imperfect, alternative. The polymetallic nodules on the seabed contain a high concentration of multiple valuable metals, making the extraction process potentially more efficient and less wasteful than terrestrial mining. The operations would occur in the remote ocean, run by technologically advanced firms under the regulation of an international body, the ISA. While the environmental risks are real, they are contained. There are no local communities to displace, no forests to clear, and no child laborers. To oppose deep-sea mining on purely ecological grounds, while implicitly accepting the human and environmental cost of the status quo on land, is a luxury we cannot afford. It is a choice to prioritize a poorly understood ecosystem we cannot see over the human suffering we can. It is an unsentimental calculation, but a necessary one.

An Irreversible Gamble with the Planet's Last Wilderness

By Ethan Yang

The argument for deep-sea mining is a classic devil's bargain, one that asks us to destroy one part of the planet to save another. It is a short-sighted and arrogant calculation that treats the deep ocean, the Earth's largest and least understood biome, as a dead, empty resource pit. This is a catastrophic failure of imagination and a betrayal of the core principles of sustainability.

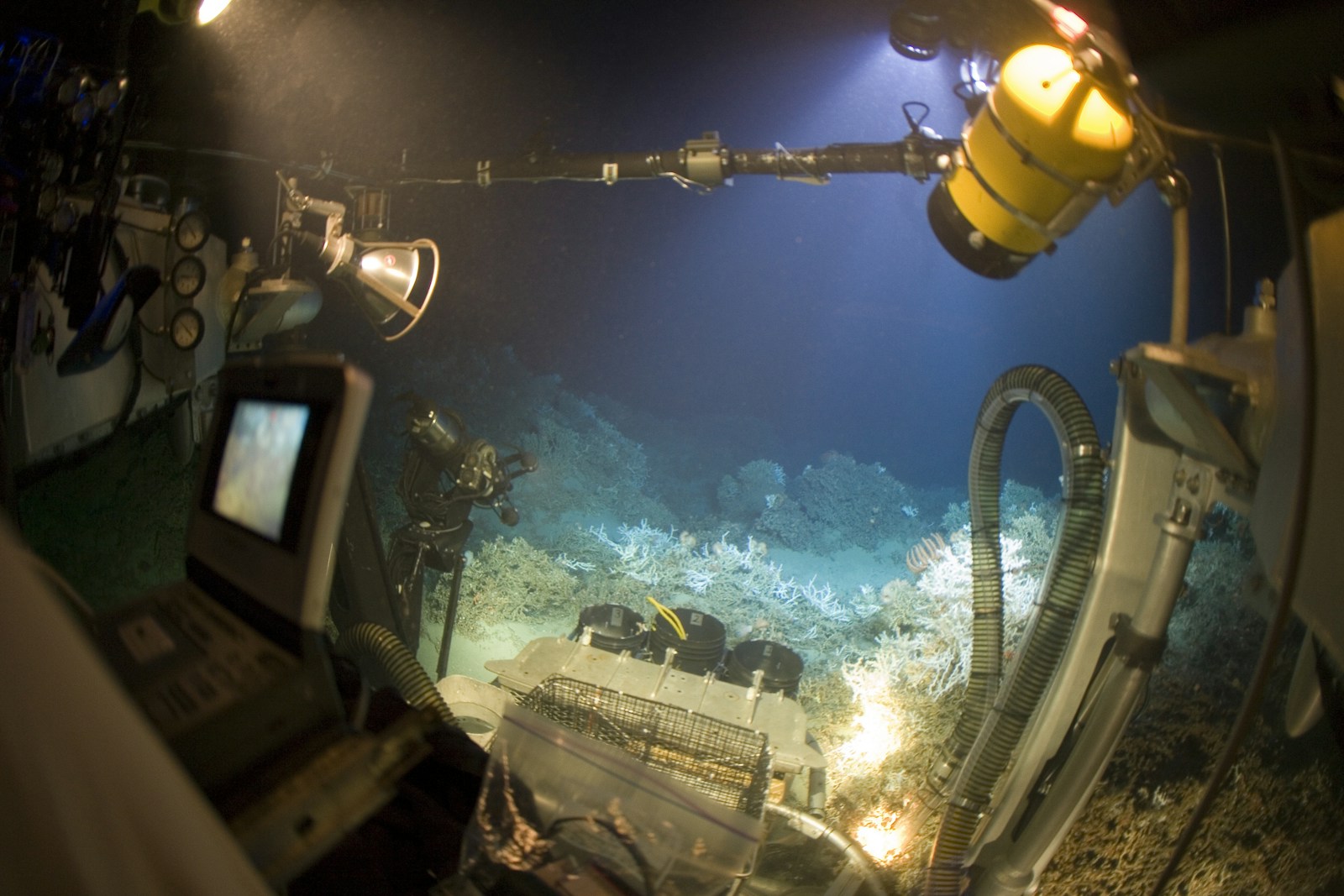

The deep sea is not empty. It is a fragile world of ancient, slow-growing corals, bizarre and unique species, and a delicate microbial ecosystem that plays a crucial role in global carbon and nutrient cycles. The mining process, which would effectively strip-mine the ocean floor and kick up massive sediment plumes, would cause a level of destruction that is, on human timescales, permanent. The 'containment' my colleague speaks of is an illusion; these plumes could drift for hundreds of kilometers, smothering marine life far from the mining site. We would be causing an extinction crisis in the dark to solve an emissions crisis in the light.

This is not a necessary evil; it is a failure of ingenuity. The push for deep-sea mining is driven by a desire to continue our linear "take-make-waste" economic model. Instead of plundering the planet's last wilderness, we should be pouring investment into the real, sustainable solutions: developing a truly circular economy for battery materials through aggressive recycling, investing in next-generation battery chemistries that use more abundant materials like sodium and iron, and designing products for longevity and repair. To argue that we must mine the deep sea is to give up before we have even truly tried. It is an irreversible gamble, and the stakes are the health of our entire ocean.