The Fever Line Moves North: How Climate Change is Redrawing the Map of Infectious Disease

When we think about the health impacts of climate change, we often picture the immediate and dramatic: the victims of heatwaves, the respiratory illnesses caused by wildfire smoke, the malnutrition caused by drought. But a quieter, more insidious health crisis is unfolding as the planet warms. The "fever line"—the geographic boundary of infectious diseases carried by insects—is steadily moving north and south from the tropics, bringing ancient plagues to new, unprepared populations.

This is not a future prediction; it is a present-day reality. Climate change is redrawing the global map of infectious disease, and our public health systems are struggling to keep up.

The Mosquito as a Climate Migrant

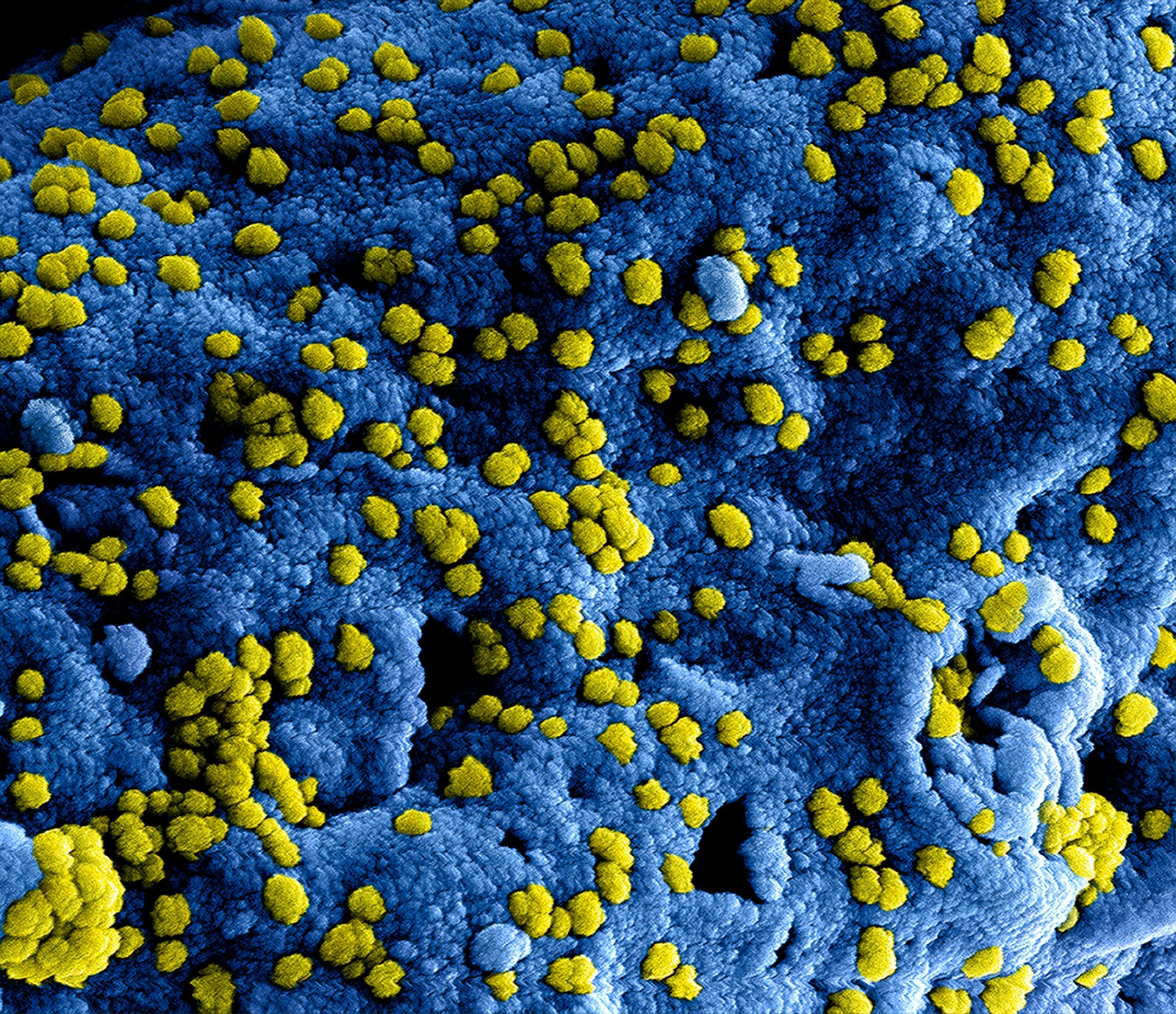

The primary agents of this change are arthropods, particularly mosquitoes and ticks. These cold-blooded creatures are exquisitely sensitive to changes in temperature and rainfall. A warmer world is, for them, a bigger world.

The case of the Aedes aegypti mosquito is a perfect and terrifying example. This species is the primary vector for a host of debilitating viral diseases, including dengue fever, Zika, chikungunya, and yellow fever. For centuries, its habitat was confined to the tropics and subtropics. But as average temperatures rise, the mosquito is finding new, hospitable homes further and further afield.

The consequences are already being felt. Dengue fever, a painful and sometimes fatal illness also known as "break-bone fever," is experiencing an explosive global surge. In 2023, the WHO reported a record number of cases, with outbreaks occurring in places that have never seen the disease before, including southern Europe. In the Americas, the disease has pushed north, with local transmission now being reported in Florida and California. The Pan American Health Organization has described the situation as the worst dengue epidemic in the region's history.

It is a similar story for other diseases. Malaria, which is carried by the Anopheles mosquito, is beginning to appear at higher altitudes in Africa and Latin America as those regions warm. Tick-borne illnesses like Lyme disease are expanding their range across North America and Europe as warmer winters allow the ticks to survive and thrive.

An Unprepared World

This geographic expansion represents a profound public health threat. The regions that these diseases are invading are often completely unprepared. Doctors in places like France or Italy are not trained to recognize the symptoms of dengue fever. Public health departments lack the surveillance and mosquito-control programs that have been in place for decades in tropical countries. And the populations themselves have no built-up immunity to these new pathogens.

This creates the potential for explosive outbreaks that can quickly overwhelm local healthcare systems. A major dengue outbreak in a large European or North American city, for example, would be a public health emergency of the first order.

Addressing this creeping crisis requires a two-pronged approach. First, we must see climate policy as health policy. The only way to stop the relentless march of these diseases in the long run is to aggressively reduce the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet.

Second, we must invest heavily in climate adaptation for our public health systems. This means building robust new surveillance programs to monitor the spread of vectors like mosquitoes and ticks. It means training doctors in non-endemic regions to recognize the symptoms of these new diseases. And it means accelerating the development of new vaccines and treatments. The race is on to reinforce our public health defenses before the fever line moves any further.